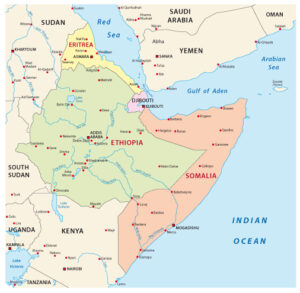

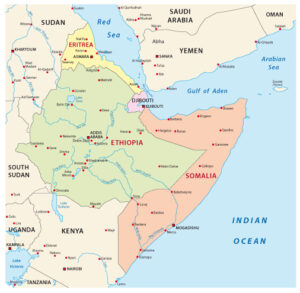

Hospitals full of malnourished children, hundreds of thousands of displaced refugees and an estimated 13 million people facing famine: the Horn of Africa is dealing with the severe impact of three consecutive seasons of failed rain. With 28 million people expected to fall victim to hunger if the dry spell does not come to a halt, even darker clouds are looming— yet none holding the desperately needed rain.

Climate-related catastrophes have been mounting in Northern Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia in recent years, which have had to deal with several severe droughts, heavy floodings in 2019 and the resulting locust swarms. These, in combination with the dire economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising food prices and ongoing armed and ethnic conflicts, have aggravated the already frail food security in the region. The ongoing drought only increases the toll on the already heavily burdened local population.

Three Consecutive Dry Seasons: a Snowballing Problem

The current drought, said to be the driest in 40 years, critically exacerbates crises such as famine. Pastoralism and farming are the main means of existence for communities in the Horn of Africa. With more than 1.5 million heads of livestock having perished due to a lack of food and water, these peoples have a mere 30 percent of their animals left that previously provided them with a livelihood. Desperate for income, farmers attempt to sell their remaining livestock, often for half the former price due to the serious malnourishment of their cattle. Simultaneously, harvests are repeatedly failing: in various areas, yields are almost 70 percent below average.

In addition to worsening the food crisis in the Horn of Africa, the drought also compounds pre-existing and new communal problems. Water and food scarcity forces people on the move, leading to conflicts over resources. As in many crises, girls are hit hardest: in their scramble for income, families increasingly resort to child marriage. As the distance these girls and young women need to travel in order to find water is increasing, sexual exploitation is on the rise as well.

With more than 5 million children facing acute malnutrition—a number that is expected to significantly rise if rains do not arrive shortly—children also fall disproportionately victim to the drought.

It is not only communities and livestock that suffer from the droughts: the sight of starved giraffes, elephants and other wildlife is not unusual anymore. Between August and December 2021 alone, Kenya lost 62 elephants due to the drought, according to Kenya’s secretary of Tourism and Wildlife Najib Balala. The search for limited water and pasture is likely to result in increased human-wildlife conflict, putting both people and wildlife at risk.

A Human-Made Drought

Unsurprisingly, climate change is said to be the driving force behind the extreme weather conditions experienced in the Horn of Africa. Although the drier conditions in East Africa are caused by “La Niña”, a natural phenomenon resulting from temperature variations in the Pacific Ocean, rising global temperatures amplify this phenomenon and its effects.

Africa contributes a maximum of 3 percent to global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it is hardest hit by the climate crisis. Between 1973 and 2013, temperatures in East Africa have risen by 0.7℃ to 1°C according to the IPCC. Since then, droughts have become more frequent and extreme in this region, attributable to extreme heat and below normal rainfall. The IPCC further found that in the increasingly impossible scenario of a maximum 1.5℃ global temperature rise, children born in 2020 in the region are likely to experience between 3 and 5 times more heatwaves than those born in 1960: a prospect that promises even more frequent extreme weather events. If global temperatures were to rise with more than 1.5℃, the prevalence of heatwaves and extreme weather conditions is likely to increase only further, with all that this entails for inhabitants of the Horn of Africa.

Competing Humanitarian Disasters

In the beginning of February, the World Food Programme launched its regional drought response program in an effort to curb the escalating humanitarian crisis. So far, however, not even half of the requested US$327 million has been raised. The FAO is experiencing similar funding shortages. With countries emerging from the pandemic, the grave situation in Ukraine, and calls for humanitarian aid in countries like Yemen, the unfolding disaster in the Horn of Africa is escaping the eyes of much needed donors.

Simultaneously, the war in Ukraine is exacerbating food scarcity in the Horn of Africa. Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia import around 90 percent of their wheat from Ukraine and Russia. This means that food and commodity prices are expected to rise beyond pandemic levels following the conflict in Ukraine, with the poor and vulnerable communities in the Horn of Africa bearing the brunt of the blow.

It is evident that immediate relief is necessary: a repeat of 2011’s catastrophical drought and famine, during which nearly 260,000 people died in Somalia alone, should be avoided at any cost. Equally important, however, is equipping communities with tools to deal with the increasing, indelible occurrence of extreme weather conditions. Unfortunately, adaptive measures for droughts and climate change are often hindered, by for instance ongoing conflicts in the region.

From wildlife to livestock, animals to people and adults to children: the current drought is putting millions of lives at risk in the Horn of Africa. Facing a fourth consecutive season with little rain, even darker times are ahead. Attention and help from the international community is paramount for averting the looming humanitarian disaster. Pulling out all the stops to meet the 1.5℃ global warming target remains as important as ever.

Luka de Laat