On the 10th of December, 2023, Argentinians will wake up to a new president: Javier Milei, a self-described “anarcho-capitalist” economist and longtime television pundit. Only recently elected to Congress in 2021, Milei’s blazing conquest of the presidency took the Argentinian political scene by surprise. Similar to other populist leaders, his candidacy was dismissed early on as no more than a political stunt.

As it turns out, Milei’s election has a lot to do not with Milei himself, but with Argentina’s political context. The financial state of the country and the disillusionment of voters after years of economic mismanagement by the two main “traditional” parties have made Argentinians open to his extreme economic ideas.

The Justicialist Party, a left-wing movement, has held the presidency for sixteen of the past twenty years. In that time, they have been unable to break Argentina’s ‘boom-bust’ cycle — a repeating loop of economic growth and deep recessions. Cambiemos, an alliance of centre-right parties, managed to create an alternance in 2015 when their candidate Mauricio Macri won the presidency. Unfortunately for them, rising inflation at the end of Macri’s first term brought the Justicialist Party back in power at the end of 2019. Today, Argentina’s inflation stands at 143 per cent.

Milei’s radical ideas to extricate Argentina from its economic turmoil are spearheaded by ambitious measures. He wants to present a balanced budget for his first year in office, which would require slashing current spending in half. He also wishes to close down 10 of the government’s 18 ministries, privatise all 34 state companies, and work towards a complete dollarization of the economy. Some of Milei’s other ideas to liberalise the economy include relaxed drug and gun laws, as well as a proposal to allow Argentinians to sell their organs on the market.

While being economically libertarian, Milei shows a more conservative side when it comes to social issues. The soon-to-be president wants to re-criminalise abortion — which was only legalised in 2020 — and denies the human impact on the Earth’s climate. He also opposes efforts to reduce inequalities between men and women.

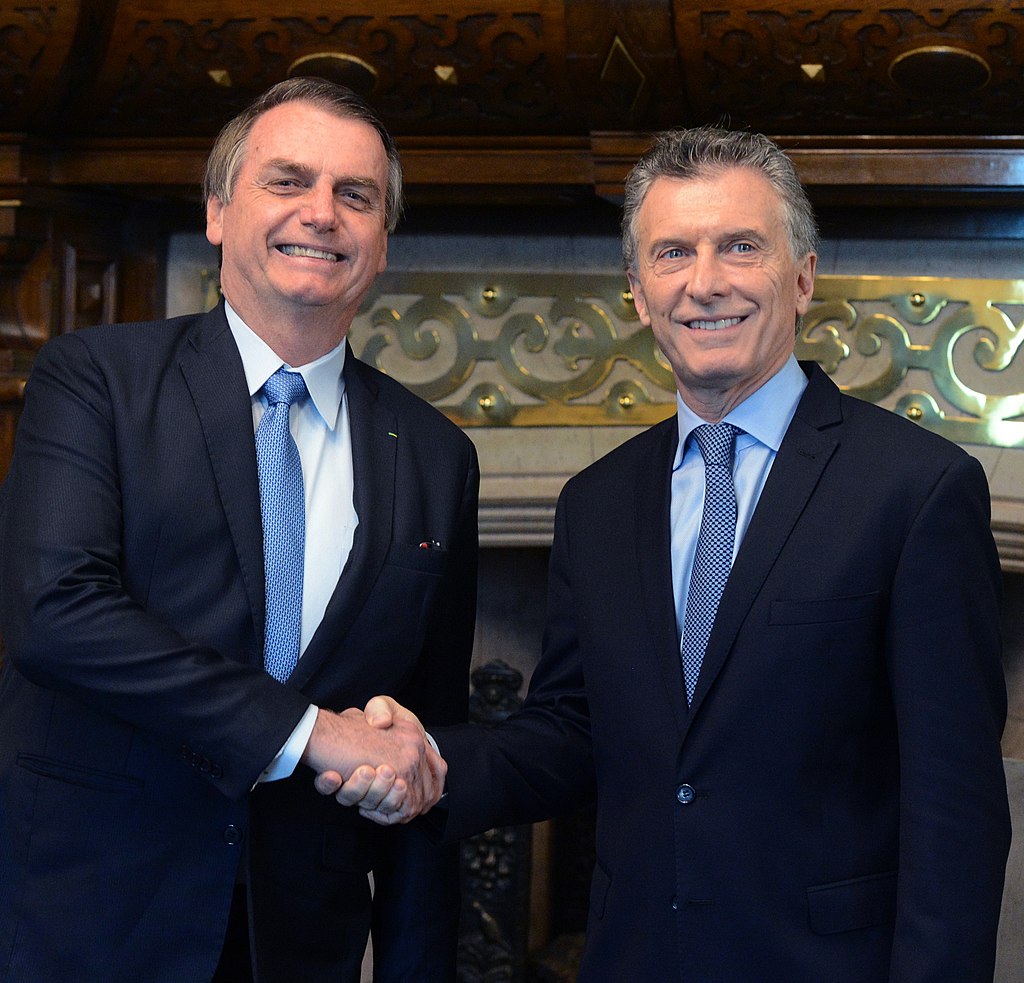

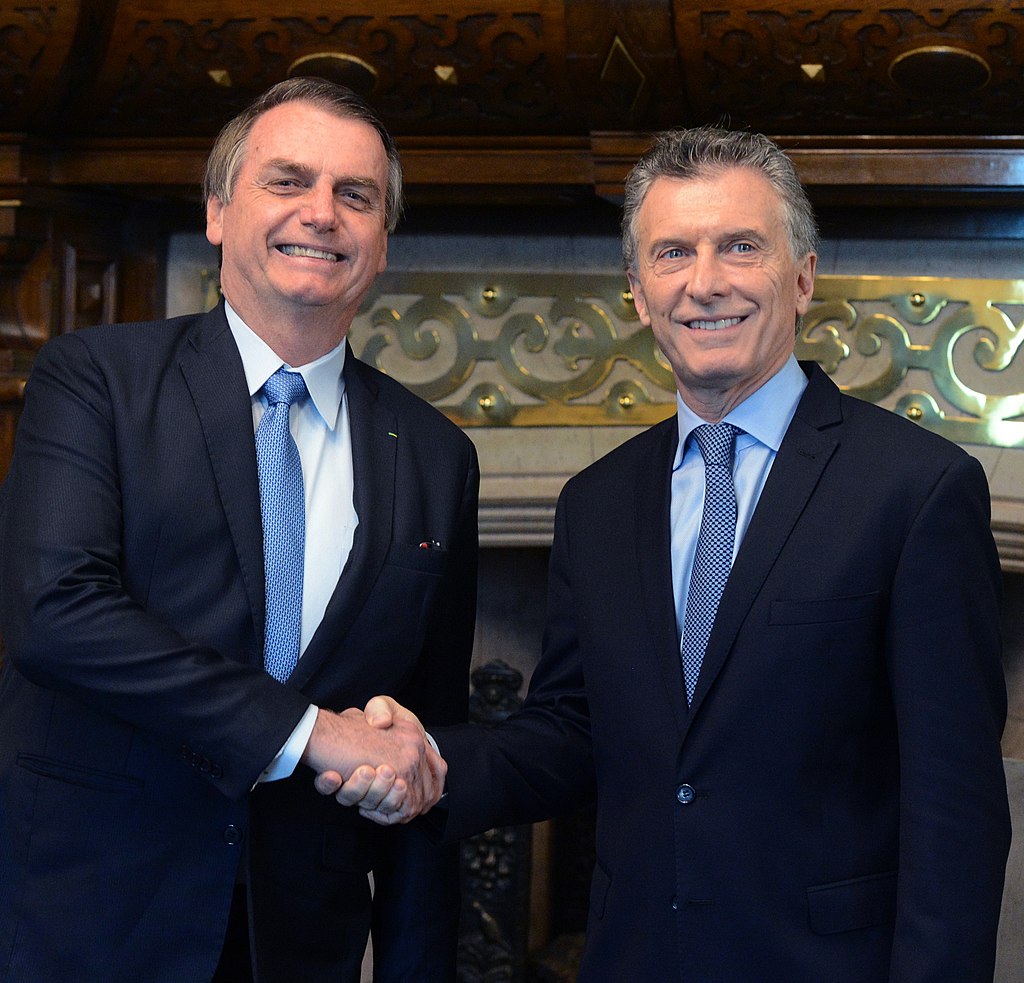

Despite his bravado attitude, Milei will have to compromise with a Congress where his party (Liberty Advances) only holds a small minority of the seats in each chamber. Some signs strongly suggest that a broad conservative alliance is on the cards. In a move that shocked many political observers, this year’s Cambiemos candidate Patricia Bullrich threw her support behind Milei after failing to qualify for the second round of the election. Since then, frequent meetings have happened between Milei and Macri, not least right after the final results were announced.

Financial markets reacted positively to Milei’s victory, similarly to how they welcomed the election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil’s 2018 presidential contest. But Milei’s rise to power resembles Bolsonaro’s in more ways than one. Both were elected on a populist, economically liberal and socially conservative platform; both saw their popularity explode against deeply unpopular mainstream politicians; and both used inflammatory rhetoric against political opponents — polarising society along the way.

On a larger scale, Milei’s election is a signal to the rest of Latin America that the same kind of firebrand populism that Bolsonaro once championed can still be politically successful today. The success of populist politicians has been visible across the region, even after the former Brazilian president was barred from running for office until 2031 at the earliest.

In Chile, José Antonio Kast, a prominent far-right politician, lost the country’s presidential election in 2021 to left-wing candidate Gabriel Boric. A controversial figure with dubious family ties (his father was a Nazi lieutenant, while his brother worked as president of the central bank under the Pinochet dictatorship), Kast remains Boric’s fiercest opponent today.

In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele has faced strong criticism for his, at times, authoritarian methods, once even sending soldiers to the Legislative Assembly to force a vote on a law his government was defending. In power since 2019, Bukele is a strong proponent of economic liberalism. El Salvador was the first country to adopt Bitcoin as a legal tender, a decision that many Salvadorans regret today. Still, Bukele remains extremely popular, mainly due to the large decrease in the country’s murder rate, which went from 38 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 to 7.8 last year. In recent months, he has been using this popularity to push against constitutional rules that forbid him from running again next year.

What Bukele’s bitcoin adoption, Milei’s dollarisation, as well as Kast and Bolsonaro’s economic policies show is a willingness to go to uncharted territories to solve their respective countries’ financial woes. At the same time, their popularity is a sign of the profound lack of physical or economic security felt by voters across Latin America. Mainstream parties, unable to address these concerns during their time in office, share some of the responsibility for the rise of populism.

The ‘Bolsonarisation’ of the region can be seen in another aspect of the public discourse — politics of memory. Picking and choosing details of a country’s history to build a particular narrative has always been a formidable political weapon. Like the former Brazilian leader, far-right figures like Milei or Kast have at times shown sympathy towards their respective countries’ authoritarian pasts or tried to downplay the crimes of their dictatorships. After US officials aired concerns about Bukele’s methods, the Salvadoran leader nicknamed himself “the coolest dictator in the world” on Twitter.

It is still too early to tell which impact Javier Milei will have on the Argentinian economy or the country as a whole. Negotiations with other parties to form a stable majority in Congress will force him to compromise on some issues. He already toned down some of his most controversial ideas between the two rounds of the election. Yet, it is safe to assume that his victory will empower similar populist figures in the region to dream even bigger, just like Jair Bolsonaro did before him. Will Latin America continue down the path of Bolsonarisation, or will this trend end with Milei? Upcoming elections next year in Mexico, El Salvador, Uruguay and other countries will decide where the region is headed.

By Antoine Vincenot

1 December 2023