The Domination of Illegal Wildlife Trade Within International Crime

Imagine a rhino, calmly poised under the shining South African sun, at peace and at home in the savannah. Its ivory horn glittering like a jewel, but valued much more than gold. Now imagine a hunter in the bushes, under the same sun, admiring the same horn…

Ivory has been a significant status symbol all over the world for centuries, and is acclaimed to have numerous medical benefits. Many would give up a kidney— or even their life savings— to get their hands on it, regardless of legality. While the rhino is protected under law, the value of its weight per kilo is staggering, and in the end, money often wins.

Rhinos are not the only species threatened by poaching and illegal trade. According to studies from the University of Oxford, more than 2,200 animal and plant species are threatened by illegal wildlife trade. A tiger, for example, is valued at around $350,000. Rather than seeing the creature as a whole being, animals subject to illegal trade and poaching are viewed by their parts, ranked from most to least valuable. The more an animal has to ‘offer’, the higher its total value. Tigers are illegally traded not just as pets and circus animals, but also as skins for rugs and carpets, teeth and claws for trinkets or jewelry, bones to make medicine or wine, and meat to eat. Fortunately, there exists organized opposition to this illegal trade. CITES–the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species founded in 1973–has been the main institution overseeing the protection of wildlife, flora, and fauna. Other organizations such as WWF also actively advocate for animal rights.

Debates on wildlife conservation often repeat ethical reasoning; it is immoral to subject the environment that preserves us to the consequences of human activity. Rarely does the conservation discussion involve economic terms, as how can one assign monetary value to life? In some contexts however, it is normalized to refer to wildlife purely as a product, beneficial for consumption and financial gain.

Illegal wildlife trade (IWT) is defined as “illegal activities harming the environment and aimed at benefiting individuals or groups or companies from the exploitation of, damage to, trade or theft of natural resources”, including both flora and fauna. IWT is regarded as poaching in severe cases resulting in the deaths of the animals. Poaching falls under environmental crimes and is considered highly illegal by both INTERPOL and the UNODC.

According to INTERPOL, IWT has become one of the largest and most lucrative criminal activities, worth $20 billion annually. The profit from this activity threatens biodiversity, communities, and security. The invasion of alien species through trade degrades the fragile equilibrium of the environment, impacting agriculture and other aspects of human and wildlife ecosystems.

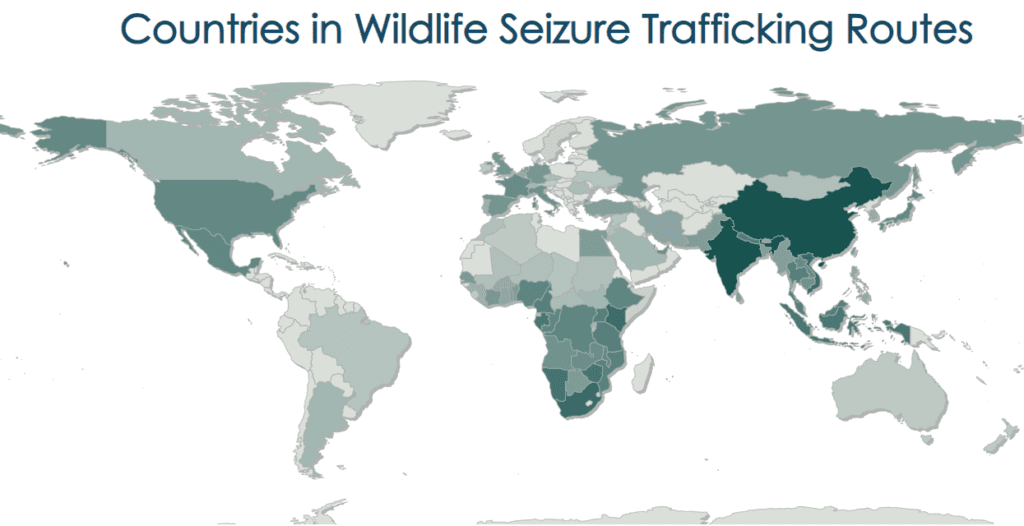

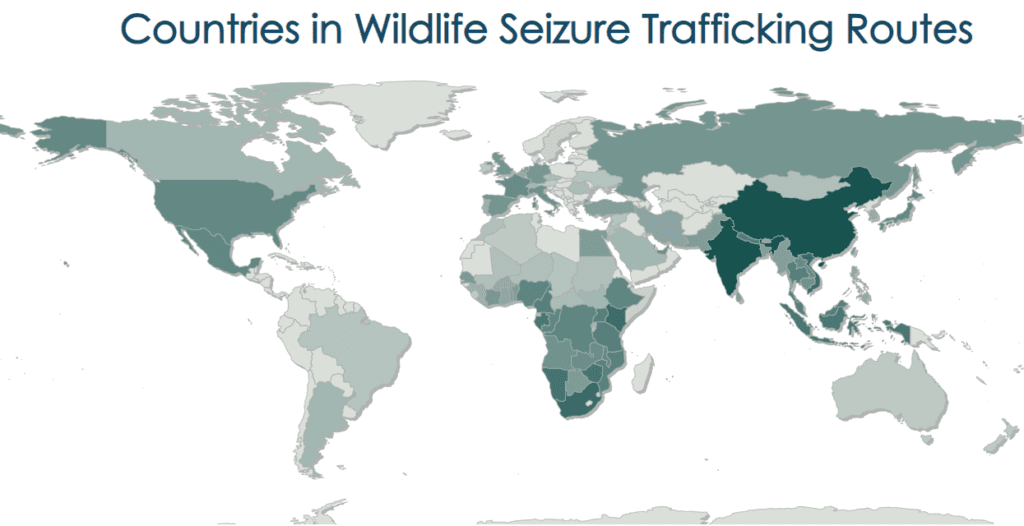

This global trade has a pattern which continues to be repeated. In IWT, the demand usually comes from rich economies, like Europe, North America and China, with the supply coming from parts of the world with rich biodiversity but poor economies, such as Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia. These geopolitical trade dynamics help constitute the flow of wildlife trade. Driving factors of IWT, namely “high profit, consumer demand, weak governance, inadequate penalties, and widespread corruption”, help maintain the inequalities and status quo of the current world order.

Poaching and illegal trade are nothing new, but they have become increasingly concerning as the frequency and severity rapidly overtake the natural limits of wildlife populations. For example, in 2020 the world was shut down due to the global pandemic COVID-19, which has been confirmed to be a zoonotic disease–meaning it derived from animals, more precisely the Southeast Asian pangolins. Ironically, it was the COVID-19 pandemic that managed to lull the IWT frenzy on account of global trade restrictions at the time. However, experts now predict a continued, if not worsened, state where trafficking of ivory, in particular, is expected to skyrocket. It seems IWT continues to dominate international crime as the ‘next big thing’. Rather than the small-scale trophy hunting that once was the norm, a significant percentage of wildlife trafficking is now the domain of organized crime groups and often coincides with drug trafficking and corruption.

The UNODC has classified the IWT supply into five categories. Fashion includes animal skins, furs and leathers. Between 2003 and 2013, studies have “identified 474 luxury fashion-related seizures [confiscations] comprising 5,607 individual items, nearly 70 percent of which were exotic leather products”, of which 84 percent were snakeskin. In another category, exotic pets, there has been an increase in the trade of live animals. These animals live out their lives in the homes of wild animal enthusiasts or are exploited in the ecotourism sector, like the elephant ‘sanctuaries’ in Thailand. The most active trade category of IWT in Asia is related to traditional medicines. Thousands of plant and animal species are believed to provide medical benefits, creating a dangerous— yet lucrative—environment for the species. For example, around 13% of traditional Chinese medicine comprises wild animal products, like tiger bones. Studies also estimate that approximately 15,000 plants are under threat due to their consumption for medical purposes. Wildlife is not only consumed for medical reasons but can also be consumed as delicacies, such as caviar or shark-fin soup. In some cases, wildlife is also one of the few sources of available nutrition for low-income rural households. Lastly, much jewelry and other fashion accessories can be found sporting the teeth or claws of endangered species, with ivory being the most valued and expensive example.

Several actors are involved in this deadly supply chain, including poachers, local dealers, and consolidators. Products get to transport facilitators who, in turn, supply the wholesaler and perhaps even a retailer, ready to sell to the customer. Customers are the most distanced actors, yet are arguably the ones to be held most accountable for enabling this illegal sector. Other contributing actors complicit in IWT are shipping companies and corrupt public officials. Given that IWT, like most criminal activities, is upheld by the simple law of supply and demand, it will likely persist as long as resources remain available.

Unfortunately, resources are dwindling, and its extensive exploitation is causing extreme negative consequences for both the natural and social world. As INTERPOL states, the consequences are “affecting vulnerable communities, jeopardizing public health and threatening the world’s natural resources”, not to mention encouraging violence, corruption, and other forms of organized crime. Every year, up to one hundred rangers are murdered in their line of duty, “protecting wildlife in their natural habitats”, and the spike in crime indicates a negative outlook on national security and stability, the well-being of local communities, and important economic sectors such as tourism. Not to mention the disastrous environmental implications–IWT is seen as one of the leading sources of natural resource overexploitation and, therefore, may be “an even bigger driver for the current biodiversity loss than climate change”.

Harm to the natural world will spell harm to every other aspect of human life. Although humans have tried to construct a separation between the natural and social worlds, the two are intertwined. It is not just a responsibility but an act of self-preservation to be invested in preserving our wildlife and to fear the loss of biodiversity. Not only do we know all too well the importance of biodiversity in keeping habitats and their species healthy and alive, but healthy soil, plants, and animals also maximize agricultural production yields and nutritional value. Furthermore, studies show that if businesses, governments, investors, and civil society work together to protect and foster biodiversity, “by 2030, this could produce a business opportunity worth $4.5 trillion in changes that support nature”. All in all, it is in our best interests to pursue sustainability within populations and ecosystems rather than overexploitation, and to do so, we must eliminate one of the most fatal metaphoric leeches: illegal wildlife trade.

By Gemma Alexandra Pettersson and Micol Zubrickaite

March 12, 2024

This article is an opinion piece whose contents represent the standpoint of its author and not UPF Lund or The Perspective’s editorial board.